Episode 12: What’s Next in Sports Analytics?

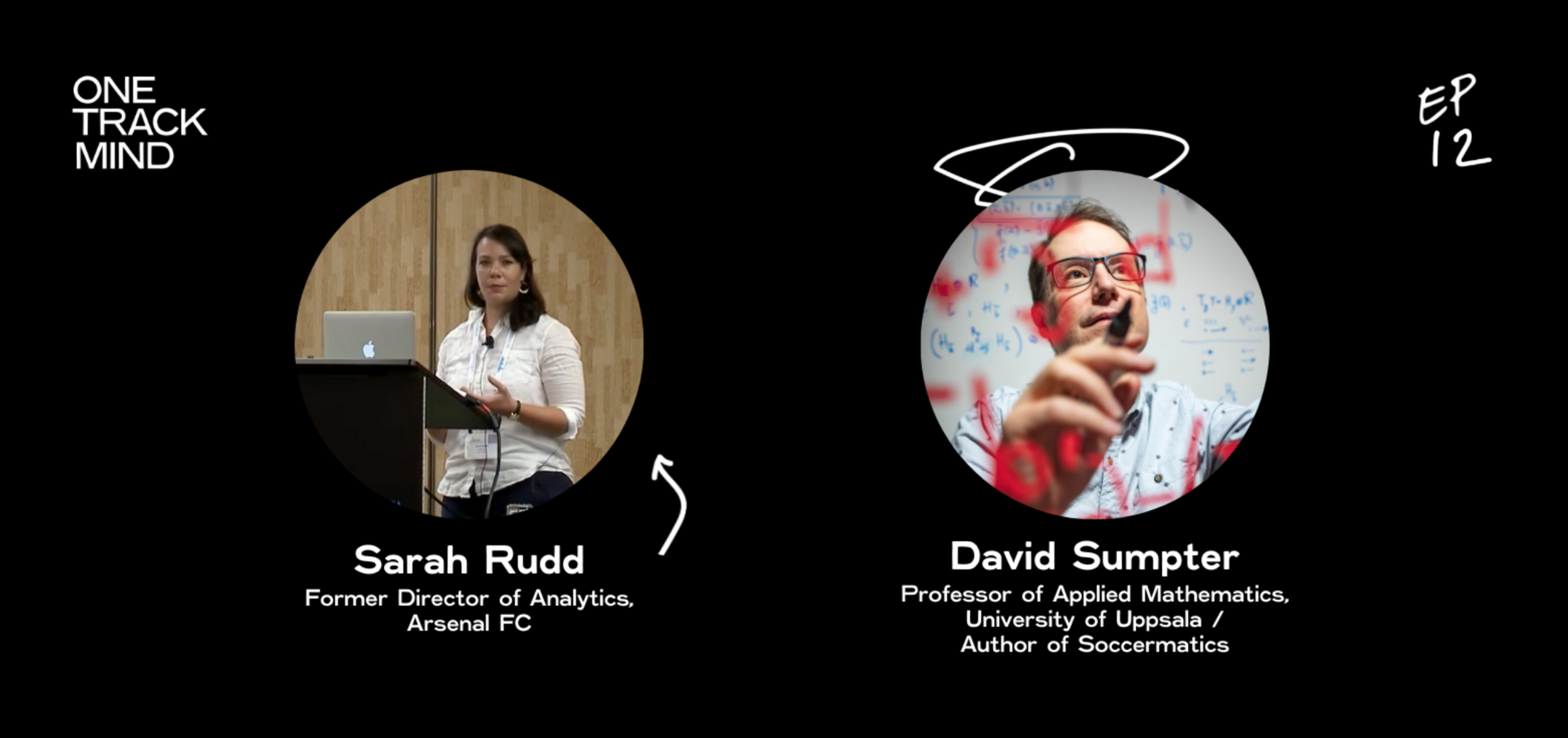

Sarah Rudd and David Sumpter come on the show to talk all things analytics –past, present and future.

Listen and subscribe on:

Spotify | Apple Podcasts | Stitcher | Overcast | Pocket Casts | RSS

Analytics is arguably one of sport's fastest growing and most exciting fields. It's something people in sport never seem to stop talking about, but do we all agree on what it actually means? To help sift through the mud and understand what we should really be asking of our sports analysts, host Professor Sam Robertson speaks to two industry legends to figure out where sports analytics can have the most impact and what's in the future for this evolving area.

First up is expert Sarah Rudd, who until recently was the Director of Analytics for none other than Arsenal FC. Next, Sam is joined by the prolific David Sumpter – Professor of Applied Mathematics at University of Uppsala and author of popular titles 'Soccermatics', 'Outnumbered' and 'The Ten Equations that Rule the World'.

Together, Sam, Sarah and David take a hard look at the current state of sports analytics and what might be on the horizon.

Full Episode Transcript

12. What’s Next in Sports Analytics?

Intro

Sam Robertson: Mention the term sports analytics and the mind of the typical person on the street will likely go straight to ‘Moneyball’, much to the annoyance of analysts everywhere. Although there's no harm in being likened to Brad Pitt, or maybe even Jonah hill, the realm of sports analytics has grown enormously since the book and subsequent movie's release.

[00:00:20] Despite still being one of the industry's newest professions, it's become far more than just finding undervalued players for clubs to sign. In fact, it's progressed so much that it's now entirely commonplace in most sports, and thoroughly ingrained in others. The increased quantification of sport, the typically broad skill sets of analysts, and the potential to make radical gains are just some of the reasons behind its growth in popularity.

[00:00:45] You could say that the role of the sports analyst is one of the most exciting professions in all of sport, but it hasn't all been smooth sailing. One look at job ads for these positions tells you there can sometimes be a lack of understanding about what the role actually is, and there can often be a disconnect between the outputs of analysts and organisational decision makers.

[00:01:05] It's also possible that one of sports analytics' greatest strengths, the absence of a single educational or accreditation pathway, could also be one of its potential threats. So is sports analytics here to stay? It certainly it looks like that's the case, but the next few years will be critical. How will its impact be evaluated? Where indeed will it actually have this impact? And above all else, what will it need to address in order to remain valued and viable?

[00:01:32] I'm Sam Robertson and this is One Track Mind.

Guest One: Sarah Rudd

[00:01:35] Hello and welcome to One Track Mind - a podcast about the real issues, forces and innovations, shaping the future of sport. On today's episode, we're asking 'What's next in sports analytics?'

[00:01:48] My first guest is Sarah Rudd. Sarah is the former Director of Analytics at Arsenal Football Club and has spent over a decade working in the field of football analytics. She was the Vice President of Software and Analytics at StatDNA before they were acquired by Arsenal and became their in-house analytics department. Prior to working in the football industry, Sarah spent several years working at Microsoft and other technology companies. She holds a Bachelor's degree from Columbia University and an MBA from the University of Washington.

[00:02:25] Sarah, thanks for joining us.

[00:02:28] Sarah Rudd: Yeah, my pleasure. Thanks for having me.

[00:02:29] Sam Robertson: Now, this is a really broad topic, like a lot of the topics that we cover on the show. I am constantly astounded as I go around the world about how people actually define the term ' sports analytics' and indeed a lot of people, particularly in your country, that don't actually like that term.

[00:02:45] So perhaps you might want to comment on that, but equally importantly, how do you define it, but also how do you delimit it in terms of maybe what it normally entails in a football club, what kind of disciplines or sub-disciplines are involved in it, what are the activities and roles that are important in this area? There's a little bit in that question, I know, but sports analytics, what does that mean to you when you hear that term?

[00:03:07] Sarah Rudd: Yeah, I mean, this is something I think I've thought a lot about over my career and I still kind of struggle to define it, but what I'm starting to kind of settle into is really sports analytics is taking a sporting match or event and trying to break it down into discretised or small little chunks so that you can analyse it and come up with something that will help your organisation come to better decision-making.

[00:03:35] And so what I kind of mean by that is it could be a bunch of things. It could be tagging a match and saying like, this is a pass, this is a shot, you know, so just breaking it down into those little events. It could be something broader. It could be saying from this point in time to this point in time we're in this phase of play and so I want to be able to add that context to my analysis, but really I think at the crux of it, it's just trying to break things down into small digestible components that will lend themselves to a more, I don't want to say objective analysis, but that's kind of what we, I wouldn't say fantasise, but maybe dream that we're doing is being objective about things. I mean, there's certainly a ton of subjectivity in terms of what we do.

[00:04:23] So in terms of like how I delimit it. Within a football club, I think there's probably four main verticals or pillars that we would operate in, in terms of sports analytics. So you'd have first team analytics where you're really trying to focus on the actual on-field performance of the team, but then you have youth development, so the on-pitch performance of the academy teams, but also player progression and player development, are they really getting what they need to become the best athlete that they can. Then you have recruitment, so being able to bring in the best players into your club, maybe optimise the sale of players leaving your club. And then lastly you have sports science.

[00:05:08] And so, I think a lot of times in the club you might have one person responsible for those, you might have multiple people responsible for those, but they're very distinct areas that there is some overlap and you would obviously hope that they're working together, but they are pretty separate verticals. And now within that, you can kind of break down those roles a little bit more and say, well, I'm responsible for first team analysis, but in order to accomplish that, I need to know about data engineering, I need to be a data scientist, I need to know about data visualisation, be a front end engineer. And again, like, it could be one person doing it, it could be multiple people doing it, but the way that I see everything is you have these verticals and then you have the skillset or the roles that kind of support that and enable you to actually operate within those verticals.

[00:05:59] Sam Robertson: Listening to you describe that, and I'm sure this isn't lost on you, that sounds like in order to fulfil that, if that indeed was one person at an organisation, they'd need to be an extremely skilled person. And I think my mind is turning to some of the job advertisements that we see online from clubs, offering these paltry salaries for people that can understand the game better than anyone, and be across those four pillars that you just mentioned there, have engineering skills, analytic skills, analytical skills in terms of model development, and of course we know that that's a pretty difficult skillset to have.

[00:06:32] And that really leads me to something I wanted to ask you off the back of your response there, which is, that clarity that some organisations don't have about what analytics actually is. And I think that's partly inherent in your response there, that it is so broad, and it could depend completely on how many people are in the organisation. Again, obviously you'd prefer to have someone responsible for data engineering, I'm sure, rather than some of the other tasks that you just mentioned there, but it's not always possible financially, or they might want to invest in that area.

[00:07:00] Do you think that breadth and the fact that we really are still in the early stages of sports analytics compared to, say, coaching or other areas, does that broadness or that breadth of that definition kind of actually hurt its ability to be adopted in some organisations or is it just a fact that it's at an early stage of its development?

[00:07:17]Sarah Rudd: Well, it can be a double-edged sword. So on the one hand, because it is so broad, it does give individuals or the club an opportunity to really be successful. So in order to be successful, you just need one person within the organisation to say, yes, this is going to be essential to how I operate, how I'm going to make decisions. Like, I'm going to be fully invested in this. And so of those four pillars, if you just have one, then you can have great impact. Whereas if it was like a little bit more narrowly defined, you might be kind of bottlenecked on one individual or two individuals. So in that sense, I think it's a little bit advantageous where there's a lot of kind of surface area to be successful.

[00:08:03] But I think, exactly as you said, where a lot of clubs have adverts for one person to do it, they might not have realistic expectations around what exactly they need to be successful. And so they think like, I'll just hire this person, like, I see this stuff on Twitter, it looks easy, one person can come in and just absolutely revolutionise things. I don't think that's the case. I think it's really quite difficult. And especially if the club has expectations that you'll work across all four of those pillars. I mean, that's just too much work for one individual. So I think if you're going to only hire one individual, you need to be really focused around what you would want them to be responsible for.

[00:08:45] You know, the kind of flip side, I guess, is that these days, there are a lot of off-the-shelf products that can kind of help out with some of these areas. So a lot of the data providers are helping out in terms of making their data as accessible as possible, so you can hold off on maybe hiring a data engineer for a little while until you fully understand what you would need.

[00:09:08] But more often than not, what I see is someone who's good in one area but not the other, trying to make things work. And then what happens is they just get what we would call technical debt, where things are just kind of cobbled together and like, it works, but you're just hoping that it survives until the off season and then you can kind of like fix it, but that's not your area of expertise and so you don't really know how to fix it. So I think then what ends up happening is like, the stakeholders are like, whoa, what are we paying this guy for? Like, everything's broken all the time. And it's just not a, I think, a successful way to operate.

[00:09:48]Sam Robertson: Yeah and ideally, I'm just thinking, you'd want that person to be able to play the long game in terms of getting some early wins in and developing something that's really user-friendly and practically applied by the coach or coaching team or the recruitment department, as you mentioned. But again, not being so inefficient that they take their eye off the engineering piece and again, as you said, the off-the-shelf products can help with that, but it really requires a mid-to-longer term vision from the club, probably more so than many other areas, and we know that we don't always get that, unfortunately.

[00:10:17]A really basic question that I think stems off all this is why sports analytics is important, full stop, and why it's even come about, I suppose. Tied into that is where it can actually have its greatest impact? You mentioned a couple of things already. And in particular, why I want to pick up on the objectivity comment that you made, because I do agree with that, but as you kind of hinted at it is there's kind of elements or shades of objectivity as well. It's almost being more objective than what's there now, that's sometimes the battle we've got.

[00:10:46] But I think the other one as well that you mentioned is across those pillars and some of the difficulties that I see is having a common language for those elements, all those pillars, to be able to speak together. And I think sports analytics can actually provide that in some cases, if it's done well. Unfortunately, some organisations you see a recruitment department actually speak or evaluate players or teams in different language to the coaching department in that same organisation. And that obviously that's a real problem. But those two areas, you know, that common language and providing more objectivity, they're two that come to mind. Do you think that's where it can have its greatest impact or are there other things that you look for?

[00:11:21] Sarah Rudd: Yeah, I think humans are inherently bad at making decisions and I think anybody who's worked in sports will say people within sports are particularly bad at making decisions. Honestly, there's a lot at stake. The pressure is high and you want to oftentimes do what you're most comfortable with, which is not necessarily the best thing. And so I think what sports analytics can help with is to try to bring some of that air of objectivity to things, but really bring in a fresh perspective and say like, you might be focusing on this because it's top of mind, it's recent, but here's the bigger picture, let's look at that.

[00:12:00] So I think recruitment absolutely is a huge area of impact where those are probably some of the most important decisions that a club is going to make. And some of the ones where I wouldn't say it's like easiest, but just ruling out bad decisions, I think is one of the things that sports analytics can really help you with.

[00:12:22]Talking about having a common language between the coaching staff, I think that's so important, but also so difficult to get right, because particularly in football clubs where there tends to be high turnover with coaching staff, your recruitment department might stay on, but your coaching staff might change. And so now you kind of have to work through that again, but it's really important that the club has that long-term vision to say, like, this is how we're going to do things and, you know, we need to work together to kind of merge what our language is and make sure that that's all connected.

[00:12:59]Sam Robertson: Yeah, as you mentioned, it comes back to that long game. If the club has, you know, obviously it's always going to be fluid, but a somewhat established framework about how they want to evaluate players that are coming into their organisation. That does allow you to have that continuity over time, which is obviously lost when a coaching department goes out.

[00:13:16] You also talked about decision-making then and I think often even when I think a decision maker, or the layperson who doesn't know a lot about sports analytics thinks about decision-making, the inclination is that it's just adding objectivity across the board, it's enhancing little decisions by bits and pieces here and there. But you made a great point then, it's actually making sure you don't get a really bad decision made or make the wrong decision, pick up that player that there should've been something obvious about them that was a red flag that you didn't bring them into the organisation.

[00:13:48] I think this is a really interesting part of sports analytics in terms of not only these kind of binary yes or no decisions about whether you choose a player or not, but there's also decisions that exist on a continuum as well, and I think there's a little nuance in that as well. And if you go through those other pillars you mentioned, there's probably a whole heap of different outputs, which make that whole job of being a sports analyst really, really interesting.

[00:14:10] You mentioned sports science at the end there, and I think we're starting to see that now. I had a good discussion in the US when I was there last, with a lot of people that have been in sports analytics for a while, and I'm not sure at that point, this was a couple of years ago now, I guess, but there was as much recognition of the value they could add to sports science as maybe there is even now a couple of years later. Is that something that you've got stuck into a little bit in your work as well?

[00:14:35] Sarah Rudd: Yeah, it's something that I think quite naturally, because in sport science you collect a lot of data that you would want to apply data analysis to. It's also something that is incredibly difficult, I think, to analyse, because if you're just looking at, say, like GPS data, or maybe the in-game tracking data, you're missing so much of that context around what's happening with the athlete, what has been their preparation going into the match, what are the demands of the coach going into that match?

[00:15:09] So it's something that we've looked into, certainly done I think a few bits of work that's been pretty interesting, but definitely an area I think that's underrated in terms of like the difficulty to actually produce something pretty useful. And there's the holy grail of an injury prediction model that, you know, I think everybody says like, I'll put this in a neural network or something like that. And then you realise like, oh, I have about 90 minutes worth of data on a player who lives 24 hours a day. Like, not going to happen.

[00:15:43]Sam Robertson: Yeah I can only nod and agree with that. You mentioned context there as well, but it's also the difficult thing with sports science as opposed to coaching or recruitment, those other areas you mentioned, is they're sometimes, and I alluded to this earlier, they're sometimes viewing the athlete or viewing the team in a completely different lens as well. And so even the context that they would apply, a sports performance person, to a certain problem is quite different to the way a coach would look at it. So you're then stuck with requiring this analyst to have different understandings of the mental models of the individuals that they're dealing with. All of this points to needing someone long-term in an organisation that has time to get into this, because it doesn't matter how technically gifted they are, they are going to need time to get across what the organisation wants.

[00:16:29] Sarah Rudd: Yep, absolutely.

[00:16:30] Sam Robertson: So with all this in mind, I want to ask you about the current state of sports analytics and whether you think it's healthy. And I know that's a relative term, but you're often described as a pioneer in sports analytics, so you've seen it evolve quite a lot. Is it getting better or worse? and, And also, are some sports leading the way better than others? Your most recent time's been in soccer.

[00:16:51] Is it getting better? It seems like it's getting certainly more publicised at least, there's more conferences coming up and there's probably more sharing, but do you have a comment on that?

[00:16:59]Sarah Rudd: Yeah absolutely and I mean, ooof, I'm coming up on, I think, close to a decade now of being in the industry. So in relative terms, that's like ancient. And if you think back about where things were when I got started, I mean, just analysing shots was seen as like technologically advanced. And these days, the things that I see in the public sphere are just so far beyond that. I mean really interesting stuff that people are doing and not just from a technical standpoint, where it's very commonplace for somebody to be able to scrape data, visualise it, analyse it. That's kind of, I think, taken for granted in terms of like minimum toolset that somebody would have these days.

[00:17:42] But I think the big difference that I'm seeing now is a far better tactical understanding of the sport. And trying to do the analysis within a tactical framework and really understand how is what I'm trying to analyse actually relatable to a coach, or relatable to a technical director, and trying to actually answer questions that those types of people would have.

[00:18:08] Whereas I think, in the early days, it was much more of like, oh, here's something interesting that I could do, but I don't really know what I would do with it. It just sounds smart. So I think that's, probably like a really big, big shift that I've noticed in the last couple of years. And this is, I think, brought on by a lot better access to data, where a lot of the data providers are giving young people the opportunity to showcase their skills. We now have tracking data available for people to analyse if they want to. So I think all of that is leading to kind of a growth in ideas.

[00:18:47] In terms of healthy, I still see maybe a lack of rigor in terms of some of the work, particularly around predictions. So if someone is trying to maybe predict whether or not a player is going to be successful after they transfer, rarely will you see any sort of like error or confidence in that. It's just kind of like, it'll go up, it'll go down. So, you know, I think that's just a pet peeve in terms of an area to improve.

[00:19:16] I think the other side of it too is like, healthy in terms of diversity. I think it's still struggling there quite a bit. I mean, you do see diversity initiatives happening and there's some progress there, but there's still a long way to go. And it's not just race and gender and background, but I think in terms of, you know, academic skills as well. I think a lot of clubs think like PhD in physics, that's what I have to hire, when there's a very broad skillset, as we talked about earlier, that you need to hire from.

[00:19:49] Communication is so, so, so important. I'm not saying go out and hire English majors, but I think there needs to be a little bit more thought in terms of what does an analyst really need to have on their CV to be successful?

[00:20:04]Sam Robertson: How are we going to improve that? I mean, we know that in jobs in sport it's invariably through a network, that's how people land jobs in sport. Occasionally obviously there's an open advertisement process, but it's definitely the exception rather than the norm.

[00:20:20]I'm surprised that it hasn't improved more as well, and I would have kind of hoped that it had, particularly because of that breadth and depth of the roles that they can have, and they can look so different at different organisations. Yeah, I don't have any easy answers.

[00:20:33] Sarah Rudd: I don't have any of the answers either. I mean, building my department, it's something that we've always kind of valued quite a bit, but at the end of the day, you know, when we have a job advert open, we only get applications from a certain demographic, and so that really limits the options. And so I think as an industry, we need to do better about keeping people interested and make them know that this is a viable career path for a lot of people.

[00:21:04] And whether that's getting more engaged with schools at an early age and talking to the kids and saying like, Hey, you know, this is a really cool application of STEM, so stick with it and if you don't end up at a sports organisation, these are the other careers that you could have as well. So I think there's a lot of outreach we can do there.

[00:21:24] There's certain initiatives, one that I'm involved in now it's called Measurables Office Hours. So they're just trying to match people in the industry with people from underrepresented backgrounds to hopefully make some networking connections or provide feedback in terms of how to get your foot in the door. But, you know, I think those are just kind of drops in the bucket. I don't really know if things will be much different in five years.

[00:21:54] Sam Robertson: That sounds like a start, and I'll certainly drop a link to that in the link to this episode, but I agree that's only just a drop in the ocean.

[00:22:00] I wanted to ask you about some of sports analytics' biggest challenges and I think that's one perhaps right there. One that I think exists, although I wouldn't say it's big in terms of difficulty, it's just something that it needs to do better, which is evaluating its impact. I talked about this with someone recently on the show around staff teams full stop, in sporting organisations. Again, sometimes I get guilty of beating up on sport a little bit because I know the area so well, but I don't think it's great in other organisations, in other industries, in some places. But I think we could do more in terms of evaluating its impact.

[00:22:37] The reason we don't is sometimes that people feel like it's a threat to maybe their freedom in their role, but also a threat to the viability of their role as well. But for the reasons we've discussed already and the breadth of areas in which it can help, I actually think it would probably increase the emphasis on sports analytics and find new homes for it. We've talked about the intersect between sports analytics and sports science already, and that hopefully does create more opportunities and more jobs in the future. But some ability to evaluate the job is important, not just how accurate was your model, for example, but all those other things that analysts do as well. Do you agree with that? And what are some other challenges you see ahead or even existing now?

[00:23:19] Sarah Rudd: Yeah, I absolutely agree with that. And I think it's so difficult because, at the end of the day, I think the value of a sports analytics department is being able to affect what happens on the pitch. So whether that's giving the coaching staff some sort of insight that changes the way that they approach their game set up, whether it's bringing in new signings that are impactful, you know, there's a lot of different ways that you can have impact as a sports analytics department.

[00:23:47] I think that one of the difficulties is that we're so far removed from the field that there's a lot of things that can change or alter our impact before it actually ends up on the field. So we could go out and say, sign this player, this player and this player. Great. Maybe that player doesn't want to come to our club. Maybe that player has wage demands that are outside of what we can currently afford. Maybe that player isn't available for a work permit. Those are all things that could impact our effectiveness. So let's say we say, okay, so our top targets aren't available, what about this guy, this guy, or this guy?. Well, maybe coaching staff doesn't like him, or they're not sure, or maybe they have an agent that doesn't like to do business with the clubs. So there's just a whole host of factors that can really impact whether or not some of the recommendations that we're making actually end up coming to fruition.

[00:24:45] Some of them are out of our control, some of them you could say maybe we need to do a better job managing up, or kind of speaking that same language, getting everything integrated. So, I think that's one of the difficulties. And I think, at the end of the day, a lot of decisions aren't necessarily like, this is what we wanted to do or that's what we wanted to do, but it's more of a compromise and saying like, okay, we're all in agreement that this is the best decision going forward. And so if it's like, well, if I was in charge of the club, I would have done something differently, but because it's a team sport we're going to go in this direction and go with that. And so again, I think it makes it a little bit more difficult to measure the impact, but for sure it's something that I think probably every department in the world could improve upon. And I think a lot of times we get asked to do that for other departments, but like, we don't want to do it to ourselves and, you know, they have the same difficulties.

[00:25:41] Yeah and in terms of other difficulties I see for sports analytics, one that is top of mind for me these days is really around longevity issues with the data. So a lot of the data providers are not very old, and so if you want to do any sort of like longitudinal analysis, you're really kind of hamstrung in terms of, well I can only go back seven years, I can only go back three years, or maybe I can go back seven years for one league, but three years for another league. And so it just kinda makes things complicated and you just, I guess, have to be patient a lot of times and say, well, we'll look at this next year or five years from now. Maybe this is unique to soccer, maybe this isn't unique to soccer, but the tactical evolution of the sport is so quick that even if you could have 10, 20, 30 years of data, would you even want to use it?

[00:26:42] And I'm sure this is something that other sports have come across and dealt with. I mean, the NBA for sure is drastically different now than it was in the eighties when I was watching it. So I don't think it's unique to football or soccer, I just don't know if enough people are talking about it and worrying about it and saying like, this is something that's really going to impact my models going forward because now everybody wants to play with a back five, whereas before only the worst teams wanted to play with a back five, that's a big shift. And are we accounting for that? That's something that I guess worries me a little bit, but it seems solvable. I don't know. It's a problem, but not the end of the world, I guess. [00:27:26] Sam Robertson: Yeah, I mean, it definitely is. And you would hope, as I think I mentioned earlier, we really are talking about early days here in terms of sports analytics. We're probably going to look back in a couple of decades time and wonder what we were doing, you know, two cave men rubbing sticks together.

[00:27:40] But I think the resolution of the data as well is an interesting point. It's very clear we're going to have better quality data on everything. We've got the sports tech, the startup industry moving at a million miles an hour, and you mentioned some of the third-party providers, they're really prolific now and organisations have so much choice with respect to who they decide to work with.

[00:28:00] Coming back to what you said in the middle there around evaluation. the example you gave then I think is a great one in terms of just the nuance and how difficult it actually would be to evaluate a sports analytics department or an individual. And maybe this is part of the reason why it hasn't been done, is you can make a recommendation or develop a process or a system or an answer to a problem, but it doesn't necessarily mean the organisation will actually act on that. And even the ability to record that over time can be problematic. Because again, if that information is shown longitudinally, or even discretely, on a particular decision to discredit, or to show that an existing decision maker, either a manager or a coach, was or is wrong, that's potentially dangerous in terms of the interpersonal relationships the analyst has as well. And that's a tricky it's a human resources piece as well. It's, kind of inherent in the role sometimes that it is inherently confrontational at times, I think. And that's another part of why maybe that piece hasn't been done.

[00:29:00]Now just before I let you go, I always try and finish on a positive note. We talked about some challenges there. Where do you think this is going to go in the near future? And I don't want to put a time limit on that, whether it's five years, 10 years. We talked about some challenges, but what's the really good stuff that hopefully is coming or you think will be coming in this area in the next little while?

[00:29:22] Sarah Rudd: Yeah, I mean I think, this isn't anything kind of groundbreaking, but as we see the generations turn over, you're going to start seeing more people in really powerful positions who really buy into this. And it's not just going to be, we have this because we want to stay ahead of the pack. It's going to be, we have this because it's essential to how I need to operate. And I think that's going to be a big shift. I think right now you'll see a couple of clubs in the world that really truly believe in this and have it fully integrated into every aspect of how they do business, but they're definitely the exception and not the norm. And I think that's going to change over the next couple of years, whether it's five years, 10 years, I don't really have a good grasp on what the timeframe will be, but I think it's coming sooner rather than later.

[00:30:18] And I think with that we're going to see a big shift in the resources being allocated to it. I think you're going to see a lot more departments that are properly staffed with the data engineers, and the data scientists, and all of that stuff to really make things hum. But then what's going to happen, I think, is right now a lot of people are just kind of operating in the same way and you can still get a competitive advantage by operating the same way as the person next to you because there aren't that many people doing it. And so, as long as there's 15 other people in the league that aren't doing anything, you're ahead of the pack. Perfect. Well, what's going to happen is as it becomes more and more commonplace to make these data-driven decisions, people are going to have to start to get really experimental and really creative in terms of how are they going to create and maintain that competitive advantage.

[00:31:16] I don't have specifics, or I don't want to go into specifics of what that looks like, but I think that's where the fun really begins and you'll start to see some really clever people doing some really clever stuff.

[00:31:27]Sam Robertson: That is a nice and optimistic tone to finish on and I agree. And I think the thread that ran through our conversation there is a little bit of stability in the long game. And I think, again, those organisations that are willing to invest now and plan now and provide certain staff time and freedom to focus on those bigger ideas and bigger questions will certainly reap the benefits down the track.

[00:31:51] On that note, Sarah Rudd, thank you for joining me on the show.

[00:31:55] Sarah Rudd: Thanks for having me. It was a great time.

Guest Two: David Sumpter

[00:32:03] Sam Robertson: My next guest on the show is Professor David Sumpter. David is author of the books Soccermatics, Outnumbered, and The Ten Equations That Rule the World. His research covers everything from the inner workings of fish schools and ant colonies, through to social psychology and segregation in society, to machine learning and artificial intelligence.

[00:32:22] David has consulted for leading football clubs and countries, including Hammarby, Barcelona and England. He works actively with outreach to schools, industry, and the social sector, and his talks at Google, TEDx, the Oxford Mathematics Public Lecture, and the Royal Institution are all available online. David, thank you for joining us!

[00:32:42] David Sumpter: Thank you for having me.

[00:32:44] Sam Robertson: We've just heard from Sarah about how she's come to define sports analytics herself after giving it considerable thought throughout her career. And I agree with some of the things she said in the fact that the term's not really nailed down yet in terms of how we define it. And I think there's a couple of reasons as to why this is the case, but before perhaps we get into those, I'll be interested in how you define and maybe even delimit that term of 'sports analytics' and perhaps whether it's even appropriate, or maybe there's a better term out there.

[00:33:17] David Sumpter: I think, I mean, I'm specifically interested in one thing. So if it's okay, I'm going to define it kind of down the lines of the things that I'm interested in. And I'm interested in the collective aspects, so how things are done in the group. So, I mean, sports analytics of course is very broad. There's all kind of ways in which you can use maths and numbers in sports, but I'm interested in how individuals act together to achieve a goal, and in football or soccer, the goal is to score goals. And so how would you manage to do that? How would you get a group of people to come together? Both tactically, both combining their skills, both mentally, physically, how do you get them to come together to achieve a goal? And then how do you use numbers to do that?

[00:34:03] So then, okay, that's what we're trying to do. We're trying to get the collective behaviour aspect. And that is where I think the mathematics comes in because maths is describing patterns. It describes how things fit together and it can describe how players in the team fit together. And so for me, sports analytics, if I come then to my definition, sports analytics is the use of mathematical tools to explain the collective. And we're probably going to go into more concrete examples as we go along, but that's the kind of overall definition of what I see sports analytics as being.

[00:34:37] Sam Robertson: And you're right, you did provide a suitably broad definition. We will narrow that down a little bit, but I don't think this is necessarily exclusive of individual sports either, but that emphasis on the collective, even in which the way a team of individuals come together, working with an individual athlete, for example, their coach and their psychologist, and I think there's a growing recognition of the complexity of sporting environments. And I know some of your work for example in, I don't know whether it's ecology, but it's certainly with animal species, is certainly relevant. And I think we're seeing a growing number of people coming from areas like ecology into sports analytics.

[00:35:11] I think some other reasons why it's a little difficult for people as well is because it's still quite new, isn't it? And it does differ so much across sports and nations and cultures. And it's also very fast moving, there's no question. And perhaps as it becomes more entrenched, more diverse roles start to become established, it will become a little bit easier to define or perhaps not, we'll find out.

[00:35:32] David Sumpter: For one thing. I mean, I gave a very kind of abstract definition at the start, but actually one thing that's very important to me is that these things are very concrete, that when you work as a sports analytics expert or a data scientist within a football club or a sports club, you're actually part of the day-to-day activities of that club, that you're involved with talking to the trainer, you're involved with talking to the people who are running the club, you're involved in talking to the players, you interact with a physiologist.

[00:36:04] And that's because, exactly as you said, because a sport is a complex system. And if you're working with a complex system, and this is what I learned from working with ants, you know, I've been a lot to Australia and I actually worked with ant biologists in Sydney in particular, but I've worked a lot on ant behaviour, on fish behaviour, and so on. If you're working with a complex system, you have to get deep inside that complex system. And my wife's just come in with a cup of coffee.

[00:36:31] Sam Robertson: Great timing.

[00:36:31] David Sumpter: So you have to sort of be embedded in it, and I think that is really key to that. It's not something you do from outside. You actually have to be part of that complex system and do it from the inside.

[00:36:44]Sam Robertson: It's a great point and that coffee looks good. Although on the other side of the world, we're just about turning to red wine at this time of the evening. So that's the beauty of doing these things all around the world at the moment.

[00:36:55] But I think that there's some great points, but I think there's a couple of other things as well that come to mind as you were speaking, which until recently, I mean, you could still argue that there is no real degree or training that you do to become a sports analyst. We're seeing people from a whole variety of backgrounds, and I mentioned ecology there and you gave some examples. I can guarantee the spiders are just as prolific here as the ants. We're seeing people from a... yeah, I think there's a lot of people from physics, for example, right now in sport. And perhaps before that, we saw a lot from economics, I think, maybe back into the nineties and the early days of sports analytics.

[00:37:31] But unless your sporting organisation's very well resourced, and perhaps even if it is, you're going to be performing multiple functions when you come into a sports organisation, you're not going to be probably doing much physics at all, even though if it might be valuable to you, whether that's state engineering, model development, visualisation. Now, your background of course is applied mathematics. So you're going to advocate for people with that type of training, of course, to come in and perform these roles, I'm sure.

[00:37:58] David Sumpter: Yeah I'm not sure I am going to advocate precisely for someone with my type of training, but what you need to have is that sort of complex thinking. And when I worked on animal behavior, we saw lots of physicists come in with their models, we saw biologists develop different models, and I think it's that type of thinking, in terms of how you create a mathematical model of something, is what you need. So yeah, of course, if you've got an applied maths training you can be good at that, but that's not necessarily the thing. It's that thinking about how do you find a good way of looking at a system, which allows us to better understand it?

[00:38:32] I mean, maybe I will become a little bit concrete, so I'll say like one thing that we worked on a lot at Hammarby when I started there, so the first thing we did is we find out what is the manager interested in, in terms of the team performance, and we use that to create our KPIs, our key performance indices.

[00:38:49] Now there is a tendency for some sort of business executives to come down to a football club and say, well, we're going to measure expected goals, and we're going to measure this, or we're going to measure that, and that's what you're going to have to live up to. And what we did is I actually went out on the training field. I found out how they were training, how they were playing, and then we started to build up measurements of the team on the basis of that.

[00:39:11] And one thing that was central for the manager was to get the ball back, quickly, in the attacking third. And so this is the sort of Pep Guardiola rule of getting the ball back after five seconds, and that was very important to our style of play. And so that was the thing that we focused on measuring. And so, first of all, we focused on measuring it so that every week we could have a report to see how that was developed. And then we started to focus on, well, how can we actually organise the team in order to get the ball back quickly? And then we use things like tracking data to find out the positions of the players. Then we started to think about what would be the optimal positions of the player and we came up with an idea, what we called the cross. And that is that when you're in the attacking third, what you do is you make a cross in midfield with your remaining players. You have your five attacking players in the top, and you have your remaining outfield players and you make them into a cross, and that covers a lot of the space if you lose the ball again. And this was our sort of form of working. I've given that example before, but there's lots of other examples.

[00:40:16] First, you start by finding out what's important, then you think about how you measure what's important, and then you sort of dig down deeper and find out how you can manipulate what's important. And you can only do that when you have a complex systems way of thinking, that you're kind of embedded inside what you're working in.

[00:40:32]Sam Robertson: Yeah and I was going to say that therefore leaves the definition open for someone from any background. It's more, the commonality running through there is the understanding of complexity, as you mentioned. And I think that should be liberating for people from any background wanting to come into sport and work and maybe have an impact, I think.

[00:40:48] The other thing you said that I wanted to pick up on, because I'm fascinated by this and I think it's not done anywhere near well enough, is that matching of a coach or a manager's or decision-maker's mental model with that of an analytical model. But also, I'm thinking of the term construct validity, but I don't want to get so much into measurement, but the ability to add the weighting to something that previously hasn't been measured with anything other than the human eye, and the example you gave then was, there was words, there was a definition in that coach's mental model, and then you sought to under underpin that with some evidence or some objective data, dare I say it, or even a framework. I think that, I mean, I know it happens now, you just gave a great example of it, but I think that's an area there's even more work that we could do in.

[00:41:34] David Sumpter: Oh, absolutely. I think it's very difficult. I mean, I was very lucky in the way that I came in working in Hammarby and I don't think that this, I mean, I work with others top clubs and countries and there it's very difficult to work in that type of way, because there's a hierarchical structure, there's a way of doing things before. They do have data people, but data people it's sort of a different role. It's more about providing some kind of visualisation for the manager to maybe look at. It's not integrated in the same way.

[00:42:04] And I think that that's what has to happen within football clubs, that they need to find a way of treating the data scientist in the same way as they maybe treat the physiologist, that they're sort of part of the team and there's an everyday interaction. So they're like the assistant trainer or something like that. And they're formulating those models and continually developing that process.

[00:42:25] But the thing is also about that is, six months later, we maybe change our style of play and that idea of getting the ball back within five seconds is not central to what we're doing and there's another type of way we're doing it and so other seasons we've worked on different models. And so you can't just like build that one model, deliver it to the club, and then go away and leave them be, because that's continually evolving as they do things. And I think that that's where the future of analytics lies, in that kind of interaction.

[00:42:56] I see actually, there's quite a lot of moaning on Twitter about, well there's always moaning on Twitter, but there's some specific moaning on Twitter about like maybe that football analytics isn't going so far, that we've seen the same visualisations time and time again. But I think it's more about, the future is about, taking that into and actioning it within inside football clubs. And that can be, for the people on Twitter I mean, it can even be in your local team. You can start to use this sort of stuff on your own team, the team that you're playing with, you can film them and do that type of analysis. So it's really about taking those visualisations and putting them into action and using them.

[00:43:37] Sam Robertson: Yeah, absolutely. And again, it's just different levels of measurement, sophistication or detail, isn't it? You can, as you said, cameras are prolific now, anyone can go out and film and record an activity and measure it. They might not have tracking data, but they can still do it through video and, let's face it, it won't be too far away that just about anyone can obtain tracking data, probably within a decade I'd imagine.

[00:43:58]I wanted to talk to you about evaluating sports analysts, because towards the end of my conversation with Sarah we talked a little bit about how to evaluate the role of the sports analyst and the example you gave then was a good one because it's not intangible, but it's quite a difficult thing to measure that example that you just gave. And I'm going to assume that it's not done particularly well in general in sport and it is a generalisation. And I don't think this is exclusive to the sports analyst, either. Some of the other roles you've mentioned as well may be similar.

[00:44:28] Now, when it comes to analysts, we probably attempted to do this very objectively. We're going to evaluate on how accurate the models that you build are, or whether your decision or your recommendation helped to avoid a decision being made. But I wonder sometimes whether we miss, not so much the softer stuff, but some of the things you mentioned there, those human components of what it is to work in this space.

[00:44:49] So these are things that aren't just true of data analytics, but perhaps in science communication, full-stop. Things like, how can I communicate something that's very challenging without losing its inherent complexity? Or is this visualisation I'm providing actually even enjoyable to the end user? I mean, and that obviously means it could be useful, not just for the decision-maker, but for fan engagement and these types of areas. And I'm interested in your thoughts here, because I know, probably more than most people working in this space, you do a lot of varied things. And so that involves communicating to different people. Authorship of books, research, teaching, working with Hammarby and other teams, presentations to the Royal Institution, fantasy football apps. So I think you're well placed to talk about this.

[00:45:32] David Sumpter: Yeah, at the start, when you were talking about sort of evaluating, and I can imagine what Sarah was talking about, evaluating is like knowing that analytics works. I'm kind of, this is sort of maybe controversial, but I'm sort of anti bothering with evaluation. I'm not really interested in that type of evaluation. Like how many points we get from using analytics, for example, because, and I think that's related to it being a complex system. The idea is that you would never not have a fitness trainer in a football team, because you need to have one. And it's very difficult to evaluate if that fitness trainer is the one that's contributing to your performance, for example.

[00:46:11] And I think it's the same with the data scientist. You should have the data scientists in the team and they should contribute and do as much as they can to make the team better, but we shouldn't be so focused on that their role should be sort of evaluating some sort of expected goals metric or something like that. It should really be about this embedment, the embodiment thing that I talked about before. And then that's reflected in my communication.

[00:46:34] I think that I maybe can appear, what do you call it, when I kind of like move between lots of different areas and sometimes I'm doing a fantasy football thing, sometimes I'm writing a book, sometimes I'm working, and that can maybe make me appear not so serious about these things, but I actually think that we don't need to take things so seriously. The idea is that what we do with Twelve with the fantasy football thing, for example, is we created an app and actually the algorithm that is the basis of that app, that originates from some of Sarah's work, where she started with making Markov chain models of football.

[00:47:10] We made an extended expected goals model of football based on possession chains, and this is one of the most advanced ways in which we can measure performance. And we said, let's actually just put that in the hands of an everyday football enthusiast, and the app you can download it at twelve.football/app, and it turns out that this app is most enjoyable or very enjoyable for people who aren't that interested in football.

[00:47:37] My daughter, who I've always tried to get interested in football, you know, and took her to train and play when she was seven or eight and she sort of ran around a little bit, but never really got into it. And I've managed to get her very interested in watching football. Now she's 18 and she watches it with her boyfriend, who also has no interest in football, and they play this app together and they gather up points. So the idea in the app is you get points based on how your player performs according to this advanced algorithm, and they can actually see and she 's sitting there like telling me who the best central midfielders are and why their ball distribution is perfect. All of these sorts of stats, that many fans, many hardcore fans, don't grasp, she's actually repeating back to me.

[00:48:18] And I think that, for me, that's an evaluation of performance - to link back to what I said at the start is that if you can get somebody engaged in that way, in watching football in a different way, then you've actually achieved something.

[00:48:32]Sam Robertson: That's a fantastic story because I think, and I don't think everyone agrees with this unfortunately, but the more people that are exposed to a sport, let's say you're a football purist and you want everyone to enjoy it, I mean, it doesn't really matter how they enjoy it as long as they enjoy it in some way, shape or form. And I think that's a good example of that.

[00:48:49] This also reminds me, what you said at the start, of an episode we had earlier this season talking about the strategy of a teams structure versus fitting it around personnel. You got me thinking a little bit, they're saying that a data person, whatever that might be termed, is inherent to the structure of a football department. And I quite liked that because again, yeah, if we do consider the football department as a complex system, it basically is impossible for us to evaluate them and then take that piece out that they had, or the influence that they had, on performance, so I like that.

[00:49:20] David Sumpter: Well I want to elaborate on that because that's something I've been thinking about a lot, and what I got asked a lot to do at Hammarby and what I'm asked to do a lot in other roles that I've had, is to evaluate things, is to say how good something is. And I really believe that that's sort of intrinsically impossible and that's what you learn in academia, that you just can't evaluate things like that. And so you're asked to do something intrinsically impossible, and so what then happens is academics and people with actual training in this, they're kind of like, well we'll just leave them to it. And you get all of these sorts of bullshit artists who come in and sell the clubs these ridiculous performance products or something like that, which tell them some number or some kind of thing, and then they go away and they base their decisions on that. Or they don't base their decisions on that.

[00:50:08] I've found that quite depressing actually, when I see the alternatives, instead of trying to get someone embedded and trying to work in detail with the particular problem, you end up with this kind of not very good management tools that come in from above and don't help anybody and take a lot of money away from the football club into pointless products. I've come out quite strong on that one, but that's a lot of my impression of working inside professional football, unfortunately.

[00:50:38]Sam Robertson: I'll ask, you know, and maybe you think about this while I say something else, but I mean, why you think that might be the case? I've seen the same as well, and I think it's fine to be strong on it because I would a hundred percent agree, and I'm sure some of the listeners would as well. But the point I wanted to make to supplement that would be, and there is some research on this, around the length of tenure of managers, not so much of staff, but the negative or potentially negative effects that can have on performance, at least in the short term. But it bugs me a little bit that a lot of staff don't get enough time either. And when they, particularly, the emphasis is so short-term as well.

[00:51:12] Some of the things we talked about earlier require time. They require time and not just time full stop, but time in someone's work schedule to be able to go and think about those things. So why do you think that managers or decision-makers, let's say, it's probably not so much just managers, but decision-makers fall for that? Is it just like everyone else that we just fall for the glitz and glamour?

[00:51:34] David Sumpter: I don't think it's the managers that fall for that because the managers don't get much input on these types of things typically. The short life of managers is also an interesting question. One reflection I have on that is that being a manager of a football team is just an incredibly tough job and you just have to work so hard, with such intense expectations of you, that I can imagine that some managers are kind of happy when they get sacked and find another challenge and can just take a breather and do something else. So that's one reflection I have on that particular.

[00:52:10] I think that's a very specific role. We often, in the media anyway, we get focused on the manager, but often the staff at a club do have longer tenures to manage to achieve things. So I'm not quite sure, I've never quite solved that manager thing. On the one hand, it might be a good idea to have a longer time with a manager, but on the other time, the pressure on that particular individual, it should be actually a rotating scheme, I think. Within a club they should have sort of 10 people and everyone should take a turn - maybe even the data scientists can have a go at being the manager for a bit. Anyway, no I'm getting a bit carried away.

[00:52:44] But so that manager thing isn't quite the problem, but the performance bit that I mentioned, I think that's just a sort of, I don't know if it's a kind of modern problem that we have this idea - I've been writing about this actually for the Barcelona Innovation Hub, it will come out later in the year - but if you think back to the whole Kahneman idea of class one and class two thinking, now that book and that research tells you a lot of different messages, but how it's read by the public is that there's this class one irrational thinking, and that's the sort of thing that football players and football managers do, and there's this class two rational thinking, and that's the sort of thing that management consultants do. And what we need to do is get rid of the class one thinking, and we get in the class two thinkers. And so then they are the people who are then offering those products to the club, but actually these class one thinkers, the people who are doing this kind of intuitive thinking, that's based on years of experience and it's based on being out there and actively part of the system.

[00:53:44] And so it's not really true that we should just throw away all of that class one stuff and bring in these kinds of class two thinkers. And the way it Kahneman is portrayed, and partly this is his own fault, but partly it's the fault of the way it's being read, is that we should take in these kind of intellectuals, management, statistic, people from outside and employ logic on it, and that's not where I'm at at all. Where I'm at is that we should put those types of people, because there is value in that type of thinking, but we should put it within the intuitive understanding that we already have of the world and use those people in there.

[00:54:22]Sam Robertson: Yeah and I think I've commented on this before on the show even, but the couple of things that come to mind with that work is that the reliability of that experience being matched with the objective, so to speak, and I'm using inverted commas there because of course, how objective is it really?

[00:54:38] But again, all of that matching over time to work out what's reliable, what's systematic differences versus random differences, these things take time as well. And all of this points back towards needing people to spend some time together to understand how they work, those mental models they have. I think it all points to not sacking a manager after three months, unless they're very, very bad.

[00:55:00] David Sumpter: In my book 'Outnumbered' I wrote a little bit about this particular problem of human decision-making versus algorithmic decision-making and I also wrote about it in Soccermatics. The one I wrote about in Soccermatics was if you're predicting the league positions next year, and it turns out basically using previous seasons' positions, so if I took the Premier League, if I say that my prediction for next season is Manchester City or Man United will come second, Liverpool, I didn't know Liverpool came third, my son informed me of this yesterday, I watched the and I was very excited that we got to the Champions League but actually Liverpool got third, and then Chelsea fourth, those will be the positions next season. And that kind of intuitive prediction of what will happen next season. All of the stuff that people are putting on and all of the models, which are kind of around that, they add a lot of unnecessary complexity, but they don't tend to make any better predictions than that basic thing.

[00:55:55] And that's what you see for League prediction, but that's what you see in a lot of the ways that people can make predictions about the future, that you can't actually improve things very much using algorithms. And so when you hear somebody telling you that they have this algorithm that will tell you the future of your football club, then you have to be very suspicious of that.

[00:56:15] Sam Robertson: I definitely agree with that, but I'm not going to be concrete on algorithms not being able to improve things at all, but I think the way that we measure the world around us in terms of the quality of those measures, and indeed, perhaps the volume in some cases is going to have a bigger impact, at least in the short term.

[00:56:32] David Sumpter: I suppose I want to go back and be clear that, of course, I think the algorithms are useful, but it comes back to exactly what analytics should be. Analytics should be a model of collective interactions and how they produce outcomes, and that model should be something which everyone has contributed to, everyone can build up an understanding of, and that we can use together, rather than a prediction of where we will be one year into the future. So that's the bit, I'm more skeptical of. The use of models in football, of course I'm all sold on, that's what you've got me here talking about.

[00:57:05]Sam Robertson: Correct. I recorded an episode last week with a colleague on complexity and you might've seen this work, it's on the visual language of complexity, it's out of a centre in the UK actually, and it boils complexity down to 16 features, which in and of themselves are quite large, so things like emergence and tipping points, hubs and levers change over time. The difficulty I have with this, and plenty of people have commented on it already, is as our understanding or at least our recognition of complexity grows in football, so too we kind of paradoxically become further away from a working model of it, I find, unless we find some tools to, not so much reduce the complexity, but make it more interpretable for the end user. And so I think that's a really tricky thing that analysts are going to face.

[00:57:55] Let's say a manager tomorrow comes in and says, yep, I'm on board with you, I understand and I agree that it's a complex system, now give me some tools, some simple tools, to navigate this. And I know there is work done in that space, but I think it's a tricky question. Like how much do you reduce before the complexity is no longer complex or it's no longer there?

[00:58:13] David Sumpter: That's a really good question for me because that is precisely what we do as applied mathematicians. So you hear all of the time philosophers or psychologists or something telling us, oh it's all a complex system, it's all a complex system, you can't do this because it's a complex system, you can't do that because it's a complex system. And that I think, this is quite arrogant of me, but that I think is what the applied mathematician does do. He or she does provide tools for dealing with complexity, and to go back to the five second rule example, that was one of them.

[00:58:48] Let me give another one. This comes from Vosse de Boode's work at Ajax. What she did is the team they have to play Champions League games and they have to play the Eredivisie, the Dutch first division games.

[00:59:03] Sam Robertson: You pronounced that better than I did.

[00:59:05] David Sumpter: And what they found is that the tempo in the Champions League is much higher than the tempo in the Dutch League, and they're playing all these games at the lower tempo and then they have to move up to the higher tempo. And so what she did is she filmed the two games and she sped up their training session games to Champions League level, their games in the Dutch First Division up to the champions league level, and she compared it to a Champions League level game, and she showed it to the players so they could actually see that their training was only 20% as fast as what was going on in the Champions League.

[00:59:42] There's not much mathematics in there, but there's a complex systems way of thinking, which says, we have this problem to do with passing tempo, how are we going to communicate it? And she used the video sped up at different levels so she could do it, and then she took this through the whole club. So she takes it down to the under nineteens and said, if you played like the men's first team in the Dutch Division this is the tempo that you would be playing at. And they can see that and they think, right, that's the tempo I have to get to.

[01:00:10] And she is the perfect example of somebody embedded in. She did a great study of it, you should watch this on the Friends of Tracking (Youube channel) , you should have her on as well and talk about this because...

[01:00:19] Sam Robertson: She is on the list!

[01:00:21] David Sumpter: Another example was penalties. There's a lot of game theoretic papers written about penalties and Google have had a go at penalties, and yeah, that's all very well and good, but what she actually did is they filmed what the goalkeeper was looking at when a penalty was taken and then how successful the goalkeeper was at saving those penalties, and they found that if the goalkeeper looked at the foot of the penalty taker, then the goalkeeper would not save the penalty as often. And so that was the first observation.

[01:00:53] And then this, I think this is the genius, right? So what they did is they built a wall up to the ball. So when the penalty taker was running up to the ball, the goalkeeper couldn't see the penalty taker, then they got the goalkeeper to train in that way. So the goalkeeper could never see the penalty taker and the goalkeeper got a much more intense training in that way. It was much more difficult. Plus, the goalkeeper learned to focus on what was important, which was the ball in

[01:01:23] Sam Robertson: Hmm, and I think Geir Jordet in Norway has done some similar work. And I think the example you gave then is a perfect one, again, of the commonality of individuals working in sport, recognising that is a complex system, that you can perturb or alter things in that system to create learning. And I happen to think that, personally, the biggest opportunity for analytics in the short term is in the design of learning environments for the athletes, and the two examples you gave then are exactly those.

[01:01:51] I think the first, the skill learning people would call representative design. So, which in simple terms is really, are you training how you play? And I think that's, in Vosse's particular club, I think that's something that they're known for, aren't they? All the way through their academy, that they have that specific way that they want to develop their athletes.

[01:02:09] David Sumpter: Exactly

[01:02:10] Sam Robertson: Yeah, I mean, certainly they're a great example of that.

[01:02:12] David Sumpter: They use science in it as well. And one thing that I've been working with a lot with players is, so now those ones don't involve so much sort of technical mathematics, but we use a model called pitch control, which shows who would get to the ball first if the ball was dropped down randomly. And so it gives a nice kind of picture of who controls what parts of the pitch.

[01:02:33] We also use the value of passes, and that's what we use in the Twelve game, for example. How much value do you get from a different pass? And these give different surfaces that we can put onto a pitch and then what we do is we can actually show these things to the players. So after they've been playing in a particular match, we take in a small group of players. Maybe we take in all the forwards, if we were interested in goal-scoring opportunities, we take in the forwards and the left and the right wingers, and we sit them in a room in a small group, so it was kind of learning experience, we put up on the screen and we show first a particular situation, which they were playing in in the recent match, then we show them the pitch control and the different value metrics for those types of things, and then we lead a discussion around those points.

[01:03:20] And what is fascinating for me there is that they began to see. So we don't want to say that the pitch control is the absolute correct answer, we want them to discuss, the typical thing is like should you have passed or should you have shot? Or you have two different passing alternatives, which of those two should you have taken? And we want them to discuss that thing, but after a bit they often start saying like, show me the answer.

[01:03:43] This is a difficult thing is they want to know what the computer says, so they'll discuss it first and then they'll say it. And then, yeah, maybe it will be like, you know, one of the players will be like, yeah, I told you so, something like this, but it's a really good tool I think for having a discussion about the decisions they've made, which becomes a lot more neutral, in a sense, they are able to have it in a much better way than just kind of arguing with each other about should you have passed or shot there? Should you have passed to me? Should you have passed to that other player?

[01:04:11]Sam Robertson: And of course the other great opportunity, and I think analytics is part of this as well, the other great opportunity is in those learning sessions to evaluate, we'll use the word evaluate, but to determine perhaps, how much learning they retain from a session like that. Again, there's opportunities everywhere for the analysis area.

[01:04:30] Now, before I let you go and get on with your day, I wanted to finish on a futuristic note, as I often do on the show, and hopefully a positive one, and where will this head in future? I've been a little critical of an area that I know you're interested in, and I know it's not the only area that you're interested in because we've spoken about many others today, but I think there's a bit of a preoccupation with tracking data at the moment in the football codes.

[01:04:53] I know we have spoken predominantly about football today and there's a whole heap of other sports that don't even have tracking data, and obviously it's kind of an example of drilling deeply down into a single area. There's a little bit of availability bias there as well, it's a data source that's readily available, it doesn't require us to think outside the square in terms of where our data's coming from. I'm being a little bit dismissive, of course, but there's probably other equally interesting and maybe potentially even more impactful areas as well, but where do you think it will head? Where would you like it to head, this area? You can be as broad as you like.

[01:05:26]David Sumpter: I'm interested in what your specific criticism is of tracking data. You mean that it won't give as much as we might have thought it would give, or?

[01:05:36] Sam Robertson: No, I don't think that. I think it's probably going to continue to give us things, although there'll be diminishing returns at some point, of course. I suppose, it's not so much the analyst's problem, it's perhaps more the fault of the way that we've pigeonholed the role and we've talked a little bit about that today, but things like, and I know organisations do this, but when should teams travel, the design of the training sessions, injury is obviously a big one, but just questions that broadening our remit, so to speak, creates more value and creates probably more jobs down the track. That's more what I mean. I mean, tracking data is fantastic and I don't think we have hit that high point yet and, let's face it, it's the closest thing to the game that people have and they're always going to be interested in it, aren't they?

[01:06:19] David Sumpter: No, I think I'm just going to take your criticism and say it's completely valid. That's what I'm interested in, right? It becomes very difficult to justify it, but I think what we found very quickly when we started working within Hammarby, that there were all sorts of questions that had nothing to do with tracking data that we needed to address first in setting up an analytics department. And I think that you're absolutely right, that tracking data is not the first one, the first thing that you need to deal with, and you can deal with a lot without tracking data.

[01:06:53] So where's the future? I mean, I'm really bad at this future question, right? So I think we used to get this when I ran a research group and looking at birds and fish and ants and so on, I remember a postdoc started in our group and he was like, "Oh, what's the really big questions that you're working on?" You know, "The other group leaders they told me about these brilliant things, and this is going to be the future", or whatever. And like, that's not what I do. That's not what I'm interested in. What I'm interested in is a problem comes in, somebody says we have to get the ball back in five seconds, or we've got to get better at penalties. A problem comes in and we find a solution to that problem. And it's very difficult in that framework to say what the future holds. It's more like, you know, as soon as you start talking about your traveling to matches and the effect of those types of things, should you get the sleep? I just start, like, thinking what could we actually do to try and solve that type of problem?

[01:07:47] So I don't really have any good things about... The future I hope is that people like me are embedded within, not just in football, but all sorts of organisations where they can be much more involved with the daily running of the things rather than giving performance measurements.

[01:08:03] The point is that it's each problem that's interesting. A problem comes up and you want to solve it, and that is kind of what drives me forward and I suppose that's what I'll still be doing right up until the day I retire.

[01:08:15]Sam Robertson: It's a nice position to be in. I think you've answered it in a different way there. I mean, I think there's all sorts of people that do future scenarios exercises, it's almost not so much what analytics looks like, it's almost what football looks like or what a sport looks like. And then are you prepared, or are you preparing a workforce, or are you preparing a mental state even, to handle those questions, which is more what you're referring to there, so I think you've still answered the question well.

[01:08:41] On that note, I'd like to thank you once again, Professor David Sumpter for coming on the show, it's been a real pleasure.

[01:08:47] David Sumpter: Well, thank you.

Final Thoughts From Sam

[01:08:51] Sam Robertson: And now some final thoughts on today's question. Whilst the definition of sports analytics continues to be elusive, whether it's data infrastructure, streamlining of processes, increasing objectivity in decision-making, or deriving new insights, its potential broad impact and opportunity for inclusivity means that it will continue to experience growth.

[01:09:15] But at a higher level, it appears that the impact of the sports analyst can be much more fundamental to an organisation. Whether they're from data science, statistics, mathematics, physics, or computer science, the analyst could provide a shared language for viewing problems across departments, by communicating complex phenomena, and in many cases, playing the role of conduit between people from different backgrounds. This should mean that over time, such roles move to becoming an inherent part of the typical performance department.

[01:09:45] However, right now there is perhaps too much being required from too few. It's simply not reasonable or sustainable to expect the typical analyst to spend their time across areas as diverse as those just mentioned. There is also room for improvement from within. As is the case with many fast-moving areas, rigour and quality control could fall by the wayside. And as we've spoken about on other episodes of this show, the diversity of individuals working in the area still leaves a lot to be desired.

[01:10:14] But perhaps the most important consideration in ensuring sports analytics is as impactful as it can be is to ensure that these individuals are given time, not only time in their work week, but in the length of their tenure. Without this, the long-term, innovative and high impact benefits are unlikely to ensue. Whilst not every sports analyst will or should be a visionary and innovator, such a vote of confidence should mean that sports analytics is not only entrenched for the years to come, but also is a key instigator in taking sports performance to new levels.

[01:10:46] I'm Sam Robertson and this has been One Track Mind.

Outro